In 2016, Fantastic Stories of the Imagination published my survey “A Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction” (now hosted here). Since then Tor.com has published 24 in-depth essays I wrote about some of the 42 works mentioned, and another essay by LaShawn Wanak on my collection Filter House. This month’s column is an appreciation of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts by Amos Tutuola.

WHERE TIME IS A LIE

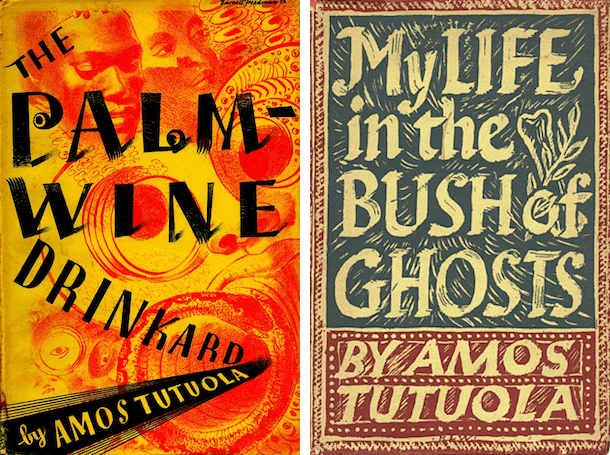

Sequel to The Palm-Wine Drinkard and often published with it as a single volume, Bush of Ghosts recounts the adventures of a nameless young boy of seven driven by war into a supernatural realm. Its short chapters have titles like “On the Queer Way Homeward” and “The Super Lady” and “Hopeless-town,” and the hero’s encounters are as weird and unprecedented as these phrases. That’s because the titular bush of ghosts is the home not merely of spirits of the dead but of paradoxical entities with hundreds of heads and televisions for hands, who live for centuries in this endless and endlessly fascinating domain. What you and I would call ghosts are here deemed “deads,” and they’re outsiders, too—though somewhat more acceptable interlopers than “earthly” beings such as the narrator.

Wandering in the bush from ghost town to ghost town, our hero is magically transformed into a cow; into a votive statue covered in blood; into a sticky, web-wrapped feast for giant spiders. During his decades-long visit he gets married twice; he also trains and works as a magistrate. Alongside references to events happening at familiar hours—8 a.m., 11 at night—Tutuola mentions the hero’s fifteen-year sojourn with a king ghost and similarly impossible stretches of time.

I LOVE THE BLUES SHE HEARD MY CRY

Time’s not the only thing out of joint in the bush of ghosts; propriety, decency, cleanliness, and order give way everywhere to dirt and chaos. Burglar-ghosts invade the wombs of women; the mouths of the Flash-eyed Mother’s myriad heads are filled with frightful brown fangs. Her whole body—indeed, the whole bush—teems with horrific effluvia: spit, vomit, excrement, and worse. The abjection of the colonized and enslaved is made hideously manifest. Even supposed merriment arises from misery—the “lofty music” that certain of the bush’s ghosts get to enjoy, for instance, is in reality the wailing of the poor young boy, who has been imprisoned in a hollow log with a poisonous snake. Like many an entertainer—Bessie Smith, Ray Charles, Michael Jackson—Bush of Ghost’s hero performs from a place of pain for the delectation of an insensible audience.

WHICH IS OUR “I”?

This book’s unusualness is striking, yet for me and other readers reared in Western and European schools of thought, it’s hard to tell what’s pure invention versus what’s the author’s extrapolation and elaboration of Yoruba traditions. Surely the church, hospital, and courts the narrator’s dead cousin has established are modern, but are they grafted onto older story stock?

Feminist works of science fiction, fantasy, and horror are, as author and editor L. Timmel Duchamp says, parts of a “grand conversation.” The same is true for works of SF/F/H by African-descended writers. Though individualistic attitudes toward authorship may prevail in our minds, we need to recognize how shared consciousness contributes to genius. We need to validate group wisdom and accept that socially-constructed systems of understanding the world inflect our every account of it. If we can accept the permeability of the membrane between self and the community, we won’t have to worry whether one or the other is this book’s source. We can relax into its wonders without classifying them.

WHAT AND WHY

Or can we? There’s also the fantasy-or-science-fiction divide to contend with. In my original history of Black SF essay I classify Bush of Ghosts as fantasy, though elsewhere I’ve argued that Ifá, the religious tradition providing much of its cosmology, is science-like. Ifá divines to ask questions and tests the hypotheses that are formed based on these questions’ answers. It records results and seeks patterns of replication in them. So perhaps speculative literature springing from Ifá is as much science fiction as an adventure involving a nonexistent time machine is?

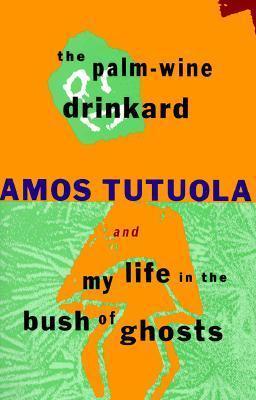

Buy the Book

The Palm-Wine Drinkard and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

WHO AND WHEN AND LETTING FLY

Here’s another important question: is Bush of Ghosts Afrofuturist? “Afro” derives from Africa, and Tutuola was most definitely an African–Nigerian, to be specific. But the term Afrofuturism was initially intended as a descriptor for creative work by U.S. descendants of the African diaspora. It was aimed at those caught up in the outflowing stream of African peoples, not those bubbling straight up from that stream’s source.

Examining this word’s other root, “future,” we find further evidence of a bad fit. Bush of Ghosts is not in any sense set in the future. Nor in the past. As I noted earlier, its story takes place outside time’s usual boundaries.

I don’t think, though, that there’s much to be gained by restricting usage of the label “Afrofuturism” to its first meaning. What we talk about changes, and so words must change, too. Maybe we can expand the definition of the word to refer to more than one hemisphere. Or maybe we can tighten it, give it a more cohesive focus—but a different one, on a different part of the world. Maybe we can leave the future behind, leave it with the past and travel beyond all considerations of temporality.

Reading Bush of Ghosts can teach us how to do that.

WHEN TO TRY

Now.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.